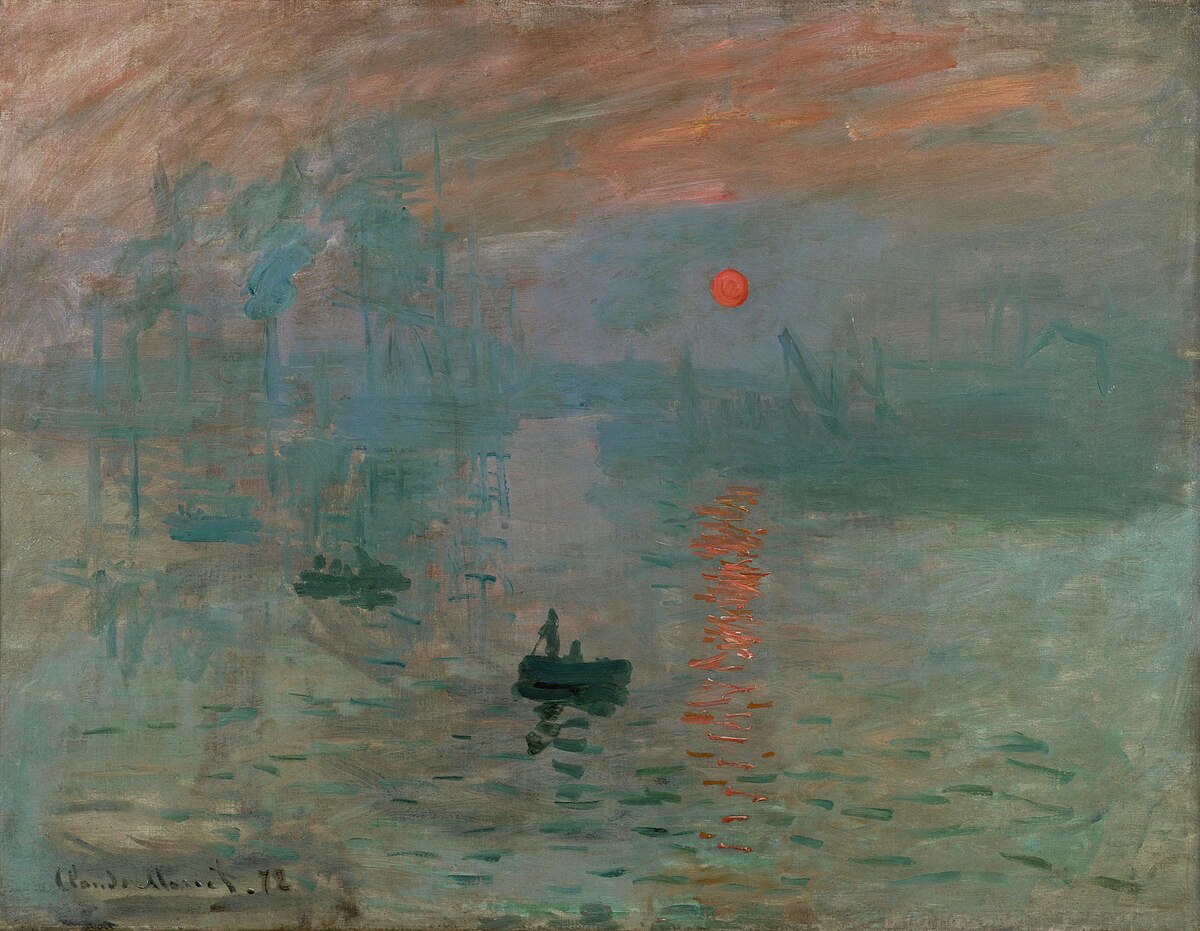

Impression: Sunrise

Claude Monet, 1872

Overview

About This Work

Painted in 1872, Impression: Sunrise (French: Impression, soleil levant) depicts the port of Le Havre at dawn and measures approximately 48 x 63 cm (oil on canvas). Today, it hangs in the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris. The painting's historical significance far exceeds its modest scale: when exhibited at the first independent Impressionist exhibition in 1874, critic Louis Leroy mockingly titled his review "Exhibition of the Impressionists," referencing Monet's title. Rather than dismissing the movement, his satire inadvertently christened what became the most revolutionary artistic movement of the 19th century. The painting captures Monet's hometown at a specific moment—early morning light breaking through fog—yet it transcends topographical description to become a meditation on perception itself. Monet had returned to Le Havre in 1872 to visit his ailing mother and created an entire series of harbour paintings exploring varying atmospheric conditions and viewpoints. Impression: Sunrise is the most famous of these, capturing not a place but a fleeting sensation: the instantaneous, subjective perception of light dissolving form into colour and atmosphere.